Archaeological methods

Geospatial analysis (GIS)

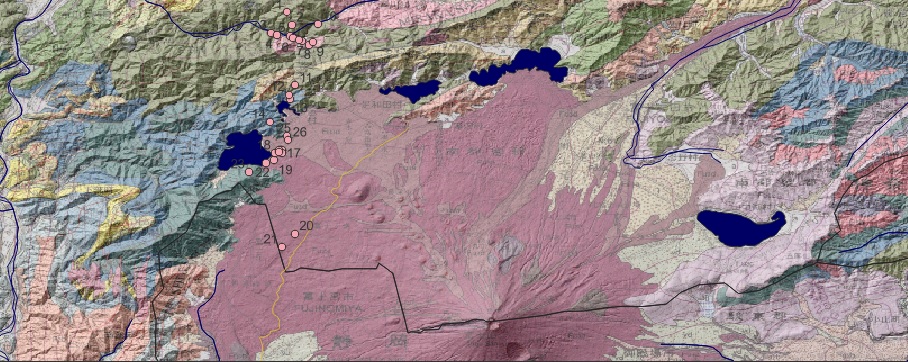

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) refers to a suite of powerful tools that can organise spatial data, as well as perform analyses on those data. Because we are interested in the human story of places and landscapes, simply collecting, organising, and analysing data is not enough to provide answers that are meaningful to a present community’s understanding of the past. In order to add value to geospatial data, this research utilises the five components of historic landscape characterisation outlined by Stephen Rippon (2012): namely the landscape as a source itself and as a means of integrating other evidence, inclusivity, focus, scale, and understanding process from form.

- The historic landscape as a source itself and as a means of integrating other evidence: ‘The primary source of information for this research is the physical fabric of the historic landscape itself. The environment, rather than sometimes arbitrary divisions of later administrative units, provides the ideal spatial and temporal framework for the careful integration of a wide range of other evidence collected within the GIS. Notably, these data are archaeological material, documentary and cartogrpahic sources, and place- and field-names. This research will do this in an interdisciplinary fashion ‘where these different strands of evidence are worked on simultaneously, and and seamlessly woven together to give one landscape history’ (Rippon, 2012, p. 3).

- Inclusivity: This research follows the definition of inclusivity provided by Rippon (2012, p. 3). ‘historic landscape analysis is applied evenly and systematically to every part of a pre-determined study area of whatever size… The approach embraces modern as well as ancient, semi-natural as well as man-made, typical as well as unusual/unique.

- Period and focus: This research intends to embrace all facets of the defined study region; however, the focus of a historic landscape approach tends to start with the present and work backwards (a ‘retrogressive’ approach) until the period when the fundamental features of the historic landscape came into being is reached (Rippon, 2012, p. 3). For the Fujigoko sub-region, this is the time of the Jōgan eruption of AD 864. However, through the geophysical methods outlined below, we are in a priveleged position to explore the landscape predating the eruption and subsequent lava flow. Through our reserach, we can both produce a historic landscape analysis while glimpsing into the past which predates the present arrangement, in come cases, by thousands of years. These glimpses will allow us to potentially measure the social and spatial response by communities during and after the disaster event.

- Scale: While research at any one of the five lakes of the sub-region might provide useful data, greater insights are provided when the subject of analysis can be intercompared with similar sites in the vicinity. A meso-scale approach is advocated here, which can utilise numerous micro-scale examples with enough detail to be useful for answering the research questions and refining the research method.

- Understanding process from form: This component is particularly important when exploring the different landscapes before and after the Aokigahara lava flow changed the hydrography of the sub-region. Because the study region is necessarily large, every individual settlement, field system, or site cannot be studied in great detail. The landscape has to be broken down into a series of generic types based on their morphology and characer, for which additional research may by analogy suggest its origins and development (Rippon, 2012: p. 4).

Geophysical survey

Marine methods

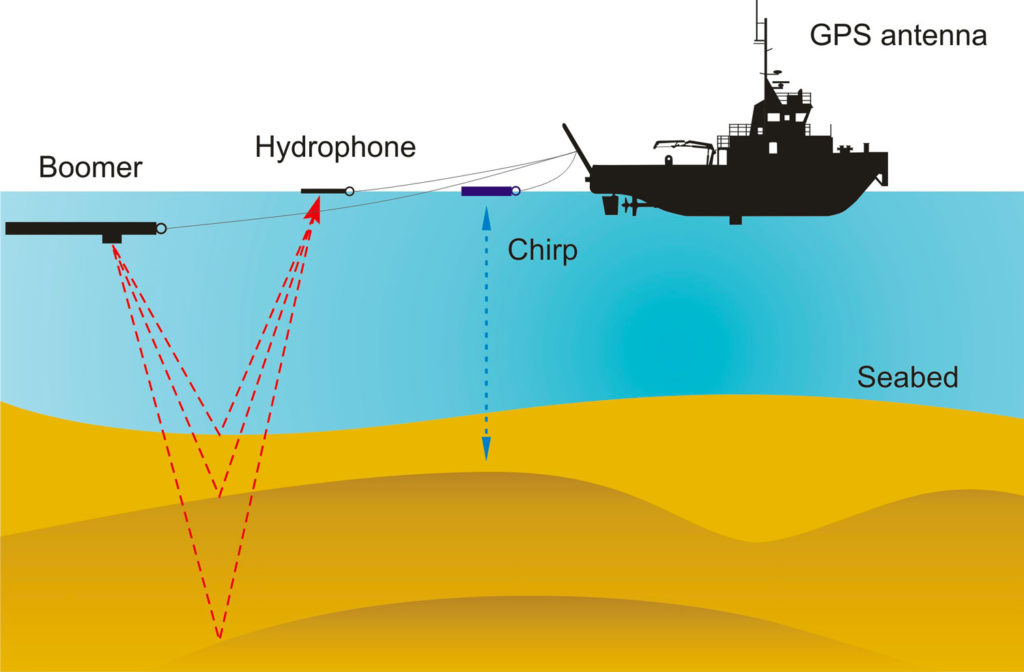

Consensus among heritage professionals is that artefacts and sites are best protected if left alone in situ. Therefore, it is increasingly important to employ non-intrusive and high-resolution techniques that can locate and identify archaeological remains buried on, or in, submerged sediments. Marine geophysical investigations are effective tools for obtaining detailed descriptions of the shallow subsurface. Additionally, these remote methods can be reapplied to identified sites or deposits, possibly also assessing their state of preservation or decay through time. The survey methodology proposes to use sidescan sonar to produce an image of the lakebed surface, and a 3D ‘chirp’ sub-bottom profiler in order to investigate archaeological deposits within the sediments themselves.

Sidescan sonar is used for mapping the seabed and identifying potential anthropogenic objects and bathymetric natural features. Sidescan sonar is a technique to efficiently create an acoustic image of large areas of the seafloor. The sonar instrument (‘towfish’) ensonifies a swathe of seabed and measuring the amplitude of the return signals, effectively creating an oblique pseudo-photograph of the seabed either side of the instrument. Objects on the seabed and information on the morphology of the surface is obtained and can be analysed. Side-scan data are frequently acquired along with bathymetric soundings and sub-bottom profiler data, thus providing a combinational glimpse of the surface and shallow structure of the seabed (Lafferty et al 2006). This research will use the sidescan sonar to identify and map potentially anthropogenic anomalies on the lakebed.

Few tools are useful in isolation. Seismic survey using 3D ‘chirp’ sub-bottom profilers reliably detect and characterise archaeological features. This method has been increasingly applied to archaeological studies, even in commercial infrastructure development contexts (Fitch et al, 2005; Grøn et al., 2007; Missiaen, 2010; Missiaen and Feller, 2008; Quinn et al, 2000). A sub-bottom profiling system detects changes in the acoustic impedance of the subsurface geology. Changes in acoustic impedance can generally be thought of as changes in density which indicate transitions from one stratigraphic sequence to another. For archaeological prospection, this transition may relate to the presence of an archaeological deposit. Sub-bottom profiler survey for archaeological prospection and paleolandscape analysis is a well-attested technique in Europe. This technique and has produced compelling results of ephemeral archaeological features in lakes (Heine, 2017) and the intertidal zone (Missiaen et al, 2017). Sub-bottom profiling of the Fujigoko sediments will allow high-resolution mapping of potentially in-situ archaeological deposits and landscape features, allowing a reconstruction of the previously subaerial landscape in the area.

Understanding cultural and religious importance

Fujigoko is a component of the Fujisan World Heritage Site, so this research can inform broader sociocultural implications of locating and elucidating submerged cultural heritage for a wide variety of stakeholders and wider sociocultural implications of this research will be considered. In particular, sites of historic or archaeological significance are not the only components contributing to the World Heritage Inscription. The World Heritage Listing is largely founded on the sacred nature of the mountain itself and the routes of pilgrimage, as well as the artistic inspiration of its topography and hydrography, including the Five Lakes. In the eighth century CE, devotion to Mt Fuji became formalised in the form of Shugendo, which fused existing practices of mountain worship with tenets of esoteric Buddhism. The nomination dossier states:

In the eight to ninth centuries, when the volcano was more active, various points at the foot of the mountain were chosen as places from which to venerate the peak from a distance as an expression of awe and respect for Asama no Okami and as a supplication to quiet the mountain’s eruptions and seismic disturbances. (Government of Japan 2012, p. 148)

The World Heritage nomination dossier recognises that the tradition of spiritual veneration of Mt Fuji extends to the present day:

In addition to the climb, worship at the Sengen-jinja shrines at the foot of the mountain and a variety of religious ceremonies and practices at sacred places on and around Fujisan- the wind caves, lava tree molds, lakes, springs, waterfalls, and so forth- still continue as living traditions. (Government of Japan 2012, p. 149)

The nomination dossier acknowledges that the cultural apprehension of the Fujisan Mountain Area draws upon the duality of the mountain and the volcano:

The awe and reverence with which Fujisan is regarded is based on Japan’s unique religious tradition of Shinto, which takes as its objects of worship the deities residing in natural objects and phenomena. As a result, a tradition was born that emphasized harmonious coexistence with the natural phenomena created by the volcano. (ibid.)

The dossier also states that prayers of thanks are offered to the mountain for bountiful harvests nourished by the springs at the base of the mountain, while the Yoshida Fire Festival had its origins in prayers to quell the eruptions. The proposed combination of marine geophysical investigation to prompt discussion of cultural values surrounding the acknowledgement of the dual power of the volcano as giver-of-bounty and as a destroyer, is a continuation of this complementary approach (ibid.).

The above raises the possibility that components of the lakebeds of the three lakes in the study area which were created by the Aokigahara lava flow could contain attributes that carry the same values as terrestrial sites, amplifying the Outstanding Universal Value of the place. Further volcanic activity and human development for the utilisation of the lake as a leisure resource represent acute threats to submerged cultural remains. By applying novel research methods to this hitherto neglected part of the Fujisan landscape, the project will assist in future preservation and management of this this finite and unique archaeological heritage.